A Decades-Old Debate

by Geri Throne / February 2022

To develop or not to develop; that’s a question Winter Park has debated for decades.

These days, with little unused space left in the city, the question has more to do with redevelopment. Should a golf course be developed as a subdivision? Should a lakefront residential lot become part of a commercial project? Should a swampy parcel be filled with dirt to build a home?

How the city should deal with such questions is the subject of six city charter amendments on the March 8 ballot. Five would set a higher bar for major land-use decisions involving wetlands construction, lakefront zoning, parks, residential density and the sale of city-owned property. A “supermajority” vote of 4-1 would be required for approval in certain situations, instead of a simple 3-2 majority. The sixth amendment would require an additional public hearing if a project changes considerably after it was submitted.

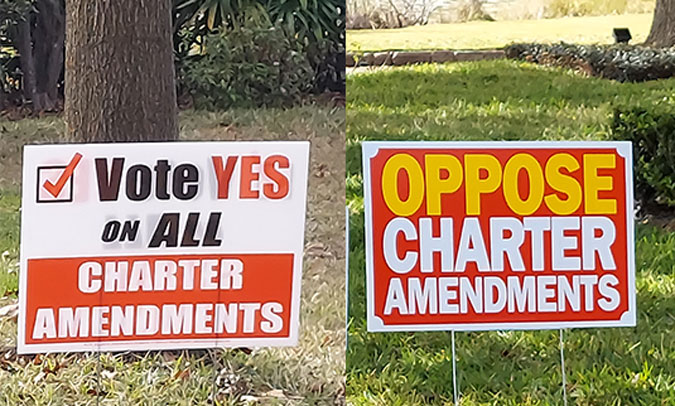

Sentiment for and against the amendments is evident. E-mails are clogging inboxes. Signs are popping up all over town.

Opponents sympathetic to development say the amendments set too high a bar and would make future land-use change impossible. Supporters concerned about preserving the city’s character say the amendments wouldn’t stop growth but would result in more compromise and public involvement for major changes.

PAST CLASHES OVER DEVELOPMENT

Tension between commercial and residential priorities has a long history in Winter Park. In the 1950s, as Interstate 4 was being designed, a push to extend Lee Road to downtown Winter Park failed as a result of residents’ objections. A decade later, neighborhood opposition squelched the dream of two consecutive mayors who wanted highway bridges built over Lakes Osceola and Killarney. The mayors’ priority was to move traffic easily to the new university east of the city.

Every decade since has seen clashes over land use. In the 1970s, the battle was over building heights. In later years, it was over road widenings, new subdivisions and the expansions of such established entities as the Winter Park YMCA, the Winter Park Hospital and Rollins College.

In the late 2000s, the biggest issues were the proposed SunRail commuter train and the Carlisle mixed-use high-rise. SunRail and its downtown station prevailed. The Carlisle – a massive condominium and retail building – didn’t. The high-rise would have loomed over Central Park in the current Post Office location. A two-year fight ended with the city buying out the developer with reserve funds and residents’ donations.

THE CURRENT CHARTER DEBATE

Among those supporting the charter changes are all current city commissioners and 1000 Friends of Florida, an organization that advocates for smart growth. The nonprofit group, which endorsed all six amendments, has advocated for a decade for supermajority votes when land-use changes can affect a city’s unique sense of place. Last year, it reaffirmed its support of supermajority votes. Its president, Paul Owens, said such changes “should have the highest level of support” and deserve more than a simple 3-2 majority. You can find the 1000 Friends of Florida document here.

Other amendment supporters say a 3-2 vote is too easy for major land-use changes unlikely to be reversed. Take the sale of rare city-owned land, says Winter Park Mayor Phil Anderson. “Once sold, the opportunity to use it for vital city operations is gone.” The same irreversibility applies to rezoning parks, he says, noting that currently it would take only three commission votes to decide to sell the West Meadow of Central Park and rezone it for offices and condos.

Anderson notes the importance of carefully considering land-use changes that could affect property values and alter the city’s quality of life. For such changes to pass with a 4-1 vote, commissioners would have to discuss them thoroughly and reach consensus. Compromise would be likely.

Opponents of the charter changes include former mayors Steve Leary and Ken Bradley and former commissioners Pete Weldon and Sara Sprinkel. Weldon filed last month to create the Winter Park Governance political action committee, which mailed out fliers against the amendments. The bulk of the PAC’s budget was contributed by real-estate developer Allan E. Keen’s company, Keewin LLC, which gave $10,000.

Weldon’s posts online describe the issue through the lens of past commission decisions. He accuses the current commission of being afraid that its use of Progress Point on Orange Avenue as a park could be overturned in the future. He sees the amendment on lakefront lots to be tied to the since-abandoned proposal for a hotel on Lake Killarney. The amendment dealing with residential density increases arose from the Orange Avenue Overlay debate, he says.

The amendments “will deter investment, paralyze Winter Park, and make serving on the city commission meaningless,” Weldon said in a Jan. 6 post.

SUPERMAJORITY VOTES NOT NEW

Central Florida is no stranger to supermajority votes. Neighboring Seminole County, for example, recently required them to dispose of natural land that the county obtained for conservation.

Supermajority votes aren’t new to Winter Park either. Previously, the city code required them for such decisions as changes to the city’s comprehensive land-use plan. But that requirement was dropped in 2013 when Ken Bradley was mayor. All mention of supermajority votes was scrubbed from the code.

Dropping the code requirements was easy because code changes need only the vote of three commissioners.

Changing the city charter, however, is much harder. Commissioners must ask voters for approval. So, if a majority of city voters approve the amendments this election, it would take a majority of city voters to remove them in the future. Think of the charter as a local constitution. It defines the essentials of how a city government works, its organization, powers and functions. Voters alone can amend it.

In the March 8 election, Winter Park voters will decide whether to set that high bar for major zoning and land-use changes in the future.

So, it doesn’t have to be all or none I’m voting in favor of 3 and against 3. I think the system in place has worked in most cases without distress to our “scale and charm”. Let’s not elevate the bar in all cases to the detriment of reasonable redevelopment.

All I needed to learn is Steve Leary and Pete Weldon are opposed to the amendments. They both pushed for the new Library project that went way way way over budget and resulted in a building that is not getting rave reviews on its functionality. The continued discussion about purchasing the post office property is insane. Furthermore, the development of the Trader Joe’s property and the current construction just down 17-92 of what originally was to be a hotel are examples of poor judgement and planning. Traffic in 17-92 is out of control and adequate parking does not exist. Lastly ( for now), maybe a super majority would have stopped the asinine Denning Dr. project that added to the traffic congestion issue at the Fairbanks intersection.

Thank you Geri for writing this great article so voters can understand the Charter Amendments. Voters please vote YES!

If you would like a YES SIGN, please contact me.

Thanks for the history lesson. I did not know a lot of that. I began in my thinking about the Charter vote when I first heard about it as a person on the fence with leaning “no”. Then as I continued reading different perspectives I moved to lean “yes”. Finally in reading this article I have come to the conclusion, given the supermajority will be required only in those 5 areas that are fundamental to the look and feel of Winter Park, if I am going to make a poor choice in the matter, I would rather error in the direction of voting “yes” thus offering the most protection to what makes Winter Park unique and have “the high bar” in place.

A “simple” 3-2 vote is ALREADY a super majority. It’s 60%. A 4-1 vote is 80%. That is too high a bar for an opinionated city like Winter Park.

Thanks, Geri, for reporting this in a cogent, objective fashion.

Geri,

While this is news to “some”, the real issue we face here in Winter Park is the lack of police presence to combat the speeding that is going on unchecked on Palmer, Lakemont and the Phelp Park neighborhoods. Check out the school crosswalk at Phelps and Palmer. The old sign that stood in the middle is gone and not replaced. Pedestrians are at risk crossing the road.

City doesn’t care. Complained to the point I am ready to get Channel 13 involved.

Tom Campbell

Tom Campbell, I contacted the city about the same exact Palmer/Phelps location. I also contacted commission members and our transportation engineer. Crickets. I asked for replacement of the paddle sign. Nothing. Cruzada is seeking greater traffic enforcement if elected. He was at the Brewers Curve citizen meeting, along with Vaya and Weaver.

I agree with 100% that speeding, reckless, aggressive cut-through traffic has eroded the quality of our life here in WP and will ultimately cost WP the reputation of being a special place to live and raise families. The former police chief never seemed to think it was anything he needed to worry about. I’m hopeful the acting chief and the next police chief will have a more realistic grasp on what lack of traffic enforcement will lead to.

Baloney. The city charter at least since 1915 has required a simple majority vote to pass all laws (ordinances) – https://bit.ly/3h4AJCW.

Super majority voting requirements removed from city codes in 2013 were removed because they were in conflict with the City Charter.

Some super majority votes are still required in the code but not for laws.

Peter Weldon. You speak as though the Charter is etched in stone. It isn’t. We, the Citizens have the ultimate control over what it does or does not say. We, not you, will decide whether these amendments would afford our property values and our quality of life greater protections. Supermajority voting requirements /protections have been included before and development oriented folks always find a way to get them out. If the amendments are passed this time, at least it will take a future charter amendment ballot referendum, decided by the voters, to remove them. (Not just a 3-2 commission vote.) Unlike the others, Amendment #6 is an homage to public notice and due process. Vote Yes if you prefer not to be blindsided by any city commission- past, present or future when certain significant changes are made at a 2nd reading. We should not even have to demand this.

I just ask myself if the people with the YES signs have any financial stake in the outcome. The answer is always no they do not. Their sole interest in a greater level of protection for citizens’ rights in land use and planning decisions. The number of affected commission decisions is quite small but the impact on the look and feel of the community is great. Every taxpayer is a stakeholder in city owned property. We deserve to have great control over when this property is sold out from under us. Building in wetlands? Rezoning park land? Your reason better be so good that you can get a 4-1 vote at minimum. The developers are in a frenzy over this. They hate anything that might stand in their way. Vote yes.

Loved reading this -vote YES!

I like all Yes Votes because many against the amendments have in the past been those such as some city commissioners responsible for the Winter Park large condos and higher than usual large buildings, many of both on the sidewalks edge or even overhanging the sidewalks. All these large unsightly buildings crowded the city and also caused more traffic.

We elect commissioners by a majority of citizen votes. The Commissioners then endorse and make decisions for us on behalf of the city. Don’t let the national pervasive party and political divisiveness, enhanced in the past few years, further confuse Winter Park’s planning, renewal, and sustainability by settling long ranging decisions from our Commission with a simple 3 – 2 vote. We need the strength of decision that can emerge from denial and/or approval with a 4 – 1 vote. This reduces the political forces that value power over change.

I support all six charter amendments wholeheartedly! The residents of Winter Park deserve this opportunity to make their voices heard by supporting and voting to protect and preserve the character of Winter Park, the city they truly love and call home.

In 1964 my Father retired from the Army and we settled in WP. I have witnessed all of the controversies Geri mentioned except the Lee Road extension issue. My first experience of government/citizen interaction (as a teenager) was a meeting where supporters and opponents of a project to four lane or otherwise expand Palmer Ave from Park Ave to Lakemont gathered. I suspect it was a “child” of the earlier Lee Road extension idea. If you know Palmer Ave you can imagine the angst in the room. I worked in local government for 35 years; I know the political process very well. The proposed amendments place a very reasonable backstop to ensure very thorough review and deliberations on matters of high importance to the fabric of WP. If a proposal covered by any of the amendments can’t garner 4 out of 5 votes, it’s probably not the best of ideas.

It’s simple: remember the Carlisle/2004. Do you want to go thru that again? Proposed 4-story building two football fields long, the size of a cruise ship slated for the current site of the West Meadow, Central Park. And yes, Allan Keen, major donor to Winter Park Governance PAC (Oppose the Charter Amendments) : the Carlisle was his project!

It does seem reasonable that significant changes that are impossible to undo should have a higher bar.

Here’s how I’m voting.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PdJm3DVg3EM

Geri conflates a fundamental governance principal with “development.” Her views and those of the people supporting these amendments only apply if you want to do everything in your power to stop development. The bias is clear and concerning.

The super majority votes in our code were removed in 2013 exactly because they were in conflict with the City Charter. They were not “scrubbed.” See: https://cityofwinterpark.org/docs/government/ordinances-resolutions/ORD2910-13.pdf?ver=1645536282948

It should be concerning to all that less than 20% of registered voters will determine an outcome that may require an 80% vote of the commission to pass meaningful legislation.

More people could vote if they only wished to do so. That is concerning. But they cannot be forced. Developers are entitled to build what the codes allow. Nothing more. If the supermajority provisions are passed, in order to build way more than codes allow, applicants will be FORCED to build consensus on the commission to win the great exceptions and variances that now are possible with a mere 3-2 vote to amend the comp plan and zoning code. We will be better for it.

Interesting how many of the entities against the Charter Amendments are related to the development industry. When Ken Bradley was in office, the Winter Park Hospital (his employer) underwent massive expansions. Conflict of interest? Of course Keen is funding the advertising for a “no vote”, because it benefits his business interests. Former mayor Steve Leary owns a property management company. Several other former mayors come from the development background. Developer profits over community?